What to Do When You See a Bear While Walking

By Darcyn Gross

Sometimes, when our father couldn’t come camping with us, my brother and I would pitch up our tent in the front yard, just a few feet from the trailer. We would build a child-like campfire and set a pot on the flames, pouring a can of Coca-Cola in to flavor the hotdogs. Even with our tent within shouting distance of our mother’s bedroom, I had this fear of waking up to an overbearing heat growing outside. The campfire still going, illuminating the frame of a burly beast pawing at the fabric next to us.

After getting sober, my father would go out into the woods behind our trailer and camp out for weeks at a time. I was always afraid that he wouldn’t come back out, that one of us would go back there and find his campsite gone, taken away by a force I had never seen in person. I imagined him in the dark, hearing the snaps of twigs and finding himself lost again, face-to-face with an overwhelming temptation.

Addiction and self-loathing are powerful urges that eat and tear at your stomach, and it’s easier to accept those than it is to try and fight back. However, to be thrown around mercilessly by these desires, while easier to accept, is not sustainable.

::

When I drink, I want to listen to music, and when I listen to music, I want to get high. I think of Pavlov’s dogs, and my mouth dampens as Elliott Smith crams himself into my canals. Drinking is easier, I told a friend, or myself, than getting high. I can still drive with a hangover, but my highs always linger into the morning and stay with me until I get home the next night.

I step out of my apartment into the puddles in front of my door. I just smoked enough to put a large animal to sleep for days, and the wind splashes rain on my face as if to dampen my dry eyes. I wait at the sidewalk’s edge, gauging which path would be emptier. I’ve just moved to the DMV, and it makes me uncomfortable; there’s a stark difference between walking through trees and walking through the city.

I don’t know what it is, but there’s just this nagging itch in the back of my head at all times. It nags constantly at my thoughts, snapping into flashes of memories that push themselves to the top. A nag similar to that of the one that probably plagued the back of my father’s head and anyone else like us: those who forego anything for one thing. But that nag lessened when I began to walk, quieted, as if it skittered down from my head, along my spine, and into my heart, as I started noticing its beat. A thump in my chest was a tug on my leg and at the tips of my fingers, and it was a scratch on my Basal Ganglia – a pathway to motivation that doesn’t feel entirely positive to me.

I had forgotten I was walking and for how long. I realized how much I was looking at my phone, not down the street, and how the rain fell on my face as I tilted my head upward. To the moist leaves stuck on grey concrete, leaves that always looked sad to me, and I saw how far I was really walking.

I don’t remember a whole lot from my childhood, and the things I do remember aren’t all that good. Depression, especially at a very early age, can make one’s memory faulty. Positive memories are harder to recall, and negative one’s stick, even after getting better. And I don’t mean ones where you tell the wrong one that you’re in love with them through intoxicated tears. I mean the one where I am binge-eating all the snacks in the house as my mother follows through and shuts the door my father left open.

Rain whispers under the flaps of my jacket as cars make half-stops at the intersection next to my apartment. The pull of my heart and the itch in my brain nags, and it nags as if to push me along my way. I stood there, waving my hand, signaling one car after the other, waiting for all the cars to clear, but after a few minutes, I knew they weren’t going to stop coming my way.

“Shit, I have been standing here too long,” I lift my leg, which seems heavier than I remembered, and the other leg awkwardly follows, “they definitely know I’m high.”

As I got halfway through the intersection, a bus lightly brakes on the opposite side of the road, facing its fluorescent lights directly at me. I began to notice the rain being spearheaded into my skin as the bus forced the wind to twist itself under my umbrella. My breathing quickly gives out. I convinced myself that I was about to be flattened, that, of course, I would die on the first day I got high in public.

::

I was in the Boy Scouts for a short period of time. I remember I never particularly liked anything that we did for activities there unless it was building wooden cars or something with prizes. At the end of the year, you would have to take this sort of quiz. It made sure you, as a boy in the scouts, knew how to do masculine things like build a fire and tie a knot for a fishing line. I knew I was going to fail this, and my father probably knew this too. While parents aren’t required to stay with the child during activities, my father did, and he helped me prepare for the quiz. We repeated every question and answered each other in turn.

“What should you do when a hole springs in your canoe?”

“Fill it with something.”

“What should you do if you see a bear while camping?”

“What color bear?”

“What should you do if you are offered drugs?”

“What kind of drugs?”

At some point during our back and forth, a scout leader sat at our table with a clipboard. He repeated the questions my father had just laid out in front of me several times. I answered each one flawlessly; I’m sure I wouldn’t have remembered the answers to these questions had I actually needed them, but right now, I was on a roll. I was close to getting every question correct until that last question, “What should you do if someone is trying to crawl into your stall in the bathroom?’

“Uhm, we didn’t go over that one.”

My father smacked me on the shoulder and laughed, “I figured you would guess that one, son.”

::

As the bus comes to a stop, I feel the air nip at the edge of my nose and the tips of my ears. I try to remember what the actual answer to that question was, what you are supposed to do when you see a bear while camping, but all I can remember is lying on my brother’s kitchen floor, my face sticking to the laminated tile. My shirt was wet from spilled liquor, and I heard my father wake up, as he often did in the middle of the night. I couldn’t move. I heard him approach my motionless body, and for a moment, I prepared my arms to be lifted up into the air. But that never happened; a cry got stuck in my throat as I felt the weight of my father’s legs glide over me. He acted as though I wasn’t there and was now sitting in the kitchen, eating something with a crinkled wrapper. I remember hating him for not helping me when he woke up to find me mumbling intoxicated thoughts on the floor, and I kept repeating things that I couldn’t have said to him then.

“Why aren’t you helping me?”

“Are you ignoring me?”

“Do I remind you of you?”

“Is this just something we have to go through?”

Once my foot hits the sidewalk, I notice how I feel out of breath. I have been mauled by that bus, I told myself; I was just too high to realize it yet. And they probably knew I was high as well, and now I’m going to die. I turn to look at the crosswalk, expecting the bus to be stopped with passengers snapping photos of the mutilated crosswalk guy. But the road was empty. The only thing pushing me away was the gentle wind. I stand there for several minutes, watching the rain cross over itself under the orange glow of a hand across the street from me. I realize I couldn’t breathe because I had recaptured an old breath, a breath that always comes back, not because I was dying.

I wasn’t thinking about how much money I wasted on a Lyft to and from Washington, spending more on the weed than getting to it, and I wasn’t thinking about how I was going to have to ask my father for more rent money to make up for the loss. Right now, I am soaked, and I am outside. There’s a nag in the back of my head, but as my clothes get heavier and stick to my body, I watch leaves chase each other in the wind, and I can’t help but think,

“Why would you want to quit this? It’s so beautiful.”

Darcyn Gross lives in Virginia with his two cats, Salem and Bjorn, doing their best to survive graduate school. He is a second-year nonfiction candidate for an MFA at George Mason University and likes to write about things he doesn’t really understand with words he can’t really pronounce. When not writing, he enjoys having good music taste, baking, and coming to terms with the spider that has been above his bed for the longest time now.

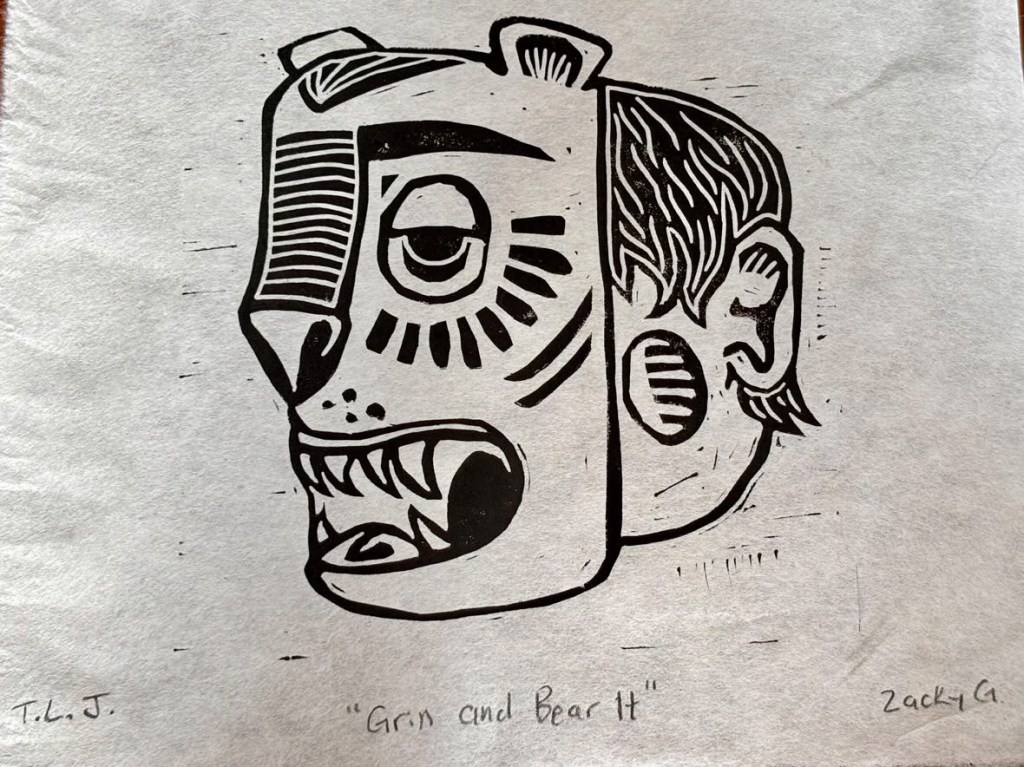

Artwork Source: “Grin and Bear It,” Zackary Gregory.

Zackary Gregory is a printmaker, teacher, and writer based in Southeastern Utah. He works as an instructor of introductory writing and literature at Utah State University’s small campus extension in Blanding, Utah. He draws inspiration from the rich tapestry of the areas history and the ongoing cultural collisions in the region. When he’s not teaching or creating visual art he’s hiking around the Bears Ears National Monument with his dog Kenny Pots, named for the ancient pottery found throughout Cedar Mesa.