Christmas Dinner

By Shannon Mulvey

There is a bone-in ribeye staring up at me from the gold-rimmed china plate. The gold flickers with the single-wick candle swaying with breaths of conversation and the passing of plates. I can only look down onto the sinewy muscle as watery blood leaks out from its corpse. I can’t fathom why this piece of meat is somehow both dry and raw.

“He’s losing his touch,” Mom whispers while wiping her hands on the Christmas-themed cloth napkins sitting on our laps.

I respond only with a hum, afraid the chef would overhear. Mom is not great at subtlety.

There are other things being passed on heavy plates around the ancient table. I grab the mashed potato bowl from the right, as the food is always passed clockwise, and feel my weak arms shake from the weight. I grab the once silver spoon now spotted with tarnish and drop the wet mix onto my plate. I try to push the potatoes as far as possible from the seeping red liquid, but the white potatoes absorb it like gauze to a bandage.

Feeling the grooves and mountains of the design on the white porcelain, I pass the bowl to the left. There’s a space to my left where my sister usually sits. She is upstairs fighting off some sort of illness. I try to imagine if I’d rather be sick upstairs, laid out on the mattress on top of rusty coils, or stuck down here with wet potatoes and mom’s comments.

My dad takes the bowl from me with clammy hands and flushed cheeks. It’s hard to know if he’s sweating from his fourth glass of wine, a fever beginning to arise, or the fact that the thermostat is set to 76. I feel my own sweat try to leak from the fleece-lined leggings I have on.

Nana speaks up from the table across from me. Our dinner seats are not assigned, but it’s unspoken. For twenty-one years we have all sat in the same seats at the same table with the same white lace tablecloth. “Well, this all just looks delicious, Bren.” Her thin hands scoop the tiniest portion of potatoes to her plate. I feel my mom make a face next to me. God, she must weigh less than 90 pounds. Does she even eat? Pop-pop is a chef for god’s sake. I hear our conversation from earlier in the evening play in my head. I don’t comment on Nana’s portion just as I didn’t comment on mom’s observation. I hate to judge what I do myself. I envy the small portion on her plate, the desire to do the same overwhelms me but the pressure of my mom is too close. God forbid she makes a comment like that about me.

Nana continues to compliment Pop-pop even as the serving size on her plate disagrees. This whole dinner disagrees with me. There are now green beans with brown tips, a buttered bun, and cranberry sauce piled with the rest of the massacre.

I curse myself at the amount of food on the plate. Maybe I wanted to hide the bloodied steak under the rest. Maybe I wanted to hide under this pile to prove I was eating. Either way, I’m royally screwed.

I can barely hear the conversation over my vision tunneling on my tortuous feast. The plain bun calls to me, despite the fact that I know it has 160 calories and 19 grams of crabs. My hands burn with the desire to log it on my Fitness app. How much can I eat of the potatoes if I’m already eating the bun? Bun is the right choice. Besides, the potatoes have absorbed the blood and now have a solid bottom layer of pink.

I pick around my plate until mom nudges me. I look up, suddenly feeling like I haven’t looked up at my family since the dinner started, and notice everyone is looking at me.

A nervous chuckle spills over my lips. “What?”

“Do you not like the food, Shannon?” Pop-pop is not one to soften his words. Luckily I was a master deflector.

“Oh! No! It’s good, great actually.” I start out strong. “I just–I’m-uh–a vegetarian now.” Wait, what?

“Since when?” Mom asks.

“I would’ve made something else,” Pop-pop says. They both speak at the same time, so I ignore mom with heat rushing to my ears. It suddenly feels 10 degrees hotter in here than before.

“It’s totally fine!” I recognize my voice has raised a couple octaves. “I won’t cause you trouble.” I feel the ridiculous sting of tears in my eyes from my own humiliation.

This is when my uncle chimes in. “Here! Have some of our vegan meat dish.” I groan internally. He brings his vegan meals every year despite disapproving glances. He walks around the table, the pine-cone and mistletoe centerpiece jingles with his steps. He dumps spongy tofu on my plate while saying, “It’s got tofu, vegan meat crumbles, and jalapenos.”

You’ve got to be kidding me. Is this really better than the bloodied steak? I suddenly envy my fever-ridden sister upstairs.

“Thanks.”

I choke down the dry tofu and try to drown myself in my water cup when the spice burns the back of my tongue. I feel Pop-pop looking at me. He has his signature frown on his face where wrinkles and a scruffy beard has made it more severe. I suddenly realize his red hoodie looks oversized on him despite his Heineken beer belly. I feel guilty.

Dinner passes quickly. Nana, mom, and I help clear the table and start the dishes. Pop-pop, dad, and my uncle go to the living room. I heard Pop-pop calling for another beer from the other room.

I open the fridge, stick my face in it just to feel cool for a moment, and walk down the creaky wood hallway to find him. He’s sitting on the couch that has golden flowers embroidered onto the beige cushions. Red, green, purple, blue lights sprinkle the room in a warm glow that matches the ambience of an orchestra’s recording of “Silent Night” playing over the radio.

Dad and my uncle aren’t here, but I can see them out the window talking outside in the wet snow. It’s just Pop-pop and I.

The smell of beer is sharp in the air as I pop off the lid for him. Spits of the bubbles in the sour drink sprinkle my clammy hand; I attempt to wipe it off on my leggings, but I know the smell will stain my skin.

“Thank you, Shannon.”

“No problem.”

We don’t talk about the meal or the weather or my sudden switch to vegetarianism. We don’t talk about how both of our clothes somehow seem oversized; one from intentional starvation, one from heart medication’s side effects. The air around us starves for substance–for a warm meal, comfort, calories–but like the emptiness inside us, we talk of nothing.

Shannon Mulvey (she/her) lives in Cumming, Georgia where she balances the joys of teaching English by day and the woes of a graduate student by night. Her works center on the uncomfortable, especially her own struggles, as she aspires to shed light on anxiety and eating disorders. When she isn’t writing, Shannon is curled up on the couch with her cat Daisy, stressing over last-minute essay-grading, or laughing with her family. This is her first publication.

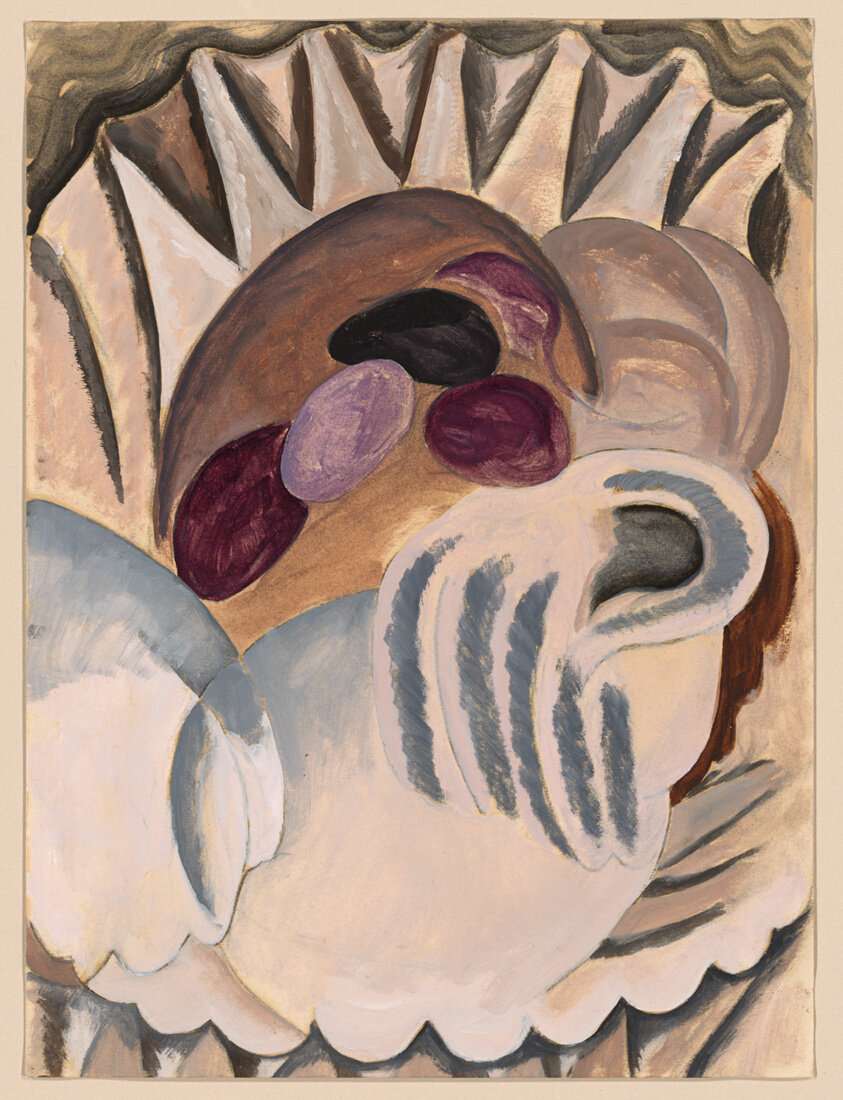

Artwork Source: “Paper Plates,” Helen Torr. From the Public Domain.